No.1 in an occasional series

REVIEW: 1970s FELICIA DE LUXE CHRONOGRAPHE

by Les Zetlein

Introduction

The trouble with reviewing watches is that you get to like it, and sooner or later you run out of watches to review. The bemused reviewer then has three choices he/she can make: stop writing reviews, buy more watches, or beg, steal or borrow interesting timepieces from whomever is foolish enough to lend them. I know (by their own confession) of many watchaholics who have a compulsion to buy whatever takes their fancy that week, and so have a never-ending supply of reviewable material. Being stingy (I like to think of it as prudent), I opted for the third choice.

In previous reviews I have mentioned my local watchmaker, who has efficiently and economically serviced my watches, and who has also from time to time sold me some vintage pieces from his 'pre-loved' display cabinet. Surely, here was an Aladdin's cave of reviewable delights! I decided to put a proposition to him: if he would loan me a watch for a couple of weeks, I would review it and put the review on the internet. He would benefit by the increased exposure this would give him and his wares; I would benefit by having different watches to try out and review. I stressed however that I would not be 'shilling' for him; I would call it as I saw it, and the reviews would be 'warts and all'. To his credit he agreed, and motioning to the cabinet said, "Take your pick". The deal was on.

Enter the Felicia

I was like a kid in a candy store. Which should be first? I

pressed my nose against the glass, my eyes darting between Omega, Eterna,

Longines, Bulova, Felicia... Felicia? I had heard of it, and

had always thought of it at the low to medium end of the Swiss watch

spectrum. The large jeweller's storechains used to carry Felicia

watches—pretty ordinary designs, nothing outstanding. I hadn't seen them

in the shops for a while, and assumed they were another victim of the quartz

phenomenon. But staring me in the face was something different.

Definitely 1970s with its squared-off cushion case, circular-brushed case top

and diver's styling. I picked it up. All stainless steel,  it

had a nice heft. A brand new rubber strap (I'd never tried one of those

before—no, honest, not even in my wilder moments). Two-register

chronograph, rotating bezel, tachymeter, telemeter, 20 atmospheres water resist,

looks absolutely mint—whoa! What have we got here? I made my

decision. "I'll take this one," I said. "OK," he

replied, "but don't go diving with it—although it looks like it, it's not

a dive watch." "But it says 20 ATU on the back!" I

protested. He made a little grimace. "I wouldn't trust it"

he said.

it

had a nice heft. A brand new rubber strap (I'd never tried one of those

before—no, honest, not even in my wilder moments). Two-register

chronograph, rotating bezel, tachymeter, telemeter, 20 atmospheres water resist,

looks absolutely mint—whoa! What have we got here? I made my

decision. "I'll take this one," I said. "OK," he

replied, "but don't go diving with it—although it looks like it, it's not

a dive watch." "But it says 20 ATU on the back!" I

protested. He made a little grimace. "I wouldn't trust it"

he said.

Under the hood

The first thing I wanted to know was "what movement is it?" A quick twist of the screw back (by my friendly local watchmaker, not me) and all was revealed—a shiny, silver-plated hand-wound Valjoux 7733. Not much evidence of decoration, but you wouldn't expect it at the original price point. Later on I did some research on the 7733, and this is what I found.

The first thing I found is that translation programs can give you peculiar results. I had located a web page about Valjoux chronograph movements, but it was in German. The translation of the opening paragraph is as follows:

"The global description elongated, approximately thousand meters highly as well as about one autohour of Geneva removes been situated mountain valley and there living humans required far more lines, than here are available. The play of the seasons pushes this landscape and the valley inhabitants, Combiers mentioned, for many centuries his salient stamp open." Er, right.

Another classic is: "The strengths of the Combiers existed in manual skill, creativity, staying power, ambition, leaving and a trueful unsurpassable gift for fiddling."

It continues in a similar vein, but I did manage to glean some useful information.

The name Valjoux comes from Vallée de Joux, a formerly inaccessible mountain region of Switzerland long associated with chronograph design and construction. Originally farmers, the locals turned to doing craft on the kitchen table during the freezing winters when they couldn't do much else, and thus a long line of watchmakers was born. (Come to think of it, they managed to do at least one other thing, otherwise the long line of watchmakers would have been a short line of watchmakers....) Anyway, in 1844 an inhabitant of the Joux Valley, one Adolphe Nicole, applied for a patent for a heart-shaped cam design which enabled the building of the first useful watch with a chronograph in 1862. (I assume this was a pocket watch.) The basic cam design is still used today, and enables the familiar start, stop and reset action now seen in all mechanical chronographs and stopwatches. (Interestingly, it wasn't until 1934 that Breitling patented the two-button chronograph, thus enabling the sequential measurement of several timed events without resetting the chrono. Up to then, with one-button chronos, the chronograph hand had to be reset before timing a second event.)

Over

the years the chronograph manufacturers improved on their own and each other's

designs. In 1939 Landeron came out with the pioneering calibres 47 and

48. Valjoux produced the 13 ligne ratchet wheel calibre from 1946, and

also made 175,000 copies of the 1948 Venus 188 cal. up to 1973. The

Valjoux 7730 (14 ligne, 6mm high) was produced until 1967. However, much

more successful were the 7733 (with 30 minute or 45 minute subdials), the 7734

(with date), and the 7736 (with 12-hour subdial) made between 1969 and

1978. Almost 2 million of these movements left the factory, destined to

tick away merrily in watches made by such names as Hamilton, Helbros, Le Jour, Memosail,

Wittenaur, and Breitling.

Over

the years the chronograph manufacturers improved on their own and each other's

designs. In 1939 Landeron came out with the pioneering calibres 47 and

48. Valjoux produced the 13 ligne ratchet wheel calibre from 1946, and

also made 175,000 copies of the 1948 Venus 188 cal. up to 1973. The

Valjoux 7730 (14 ligne, 6mm high) was produced until 1967. However, much

more successful were the 7733 (with 30 minute or 45 minute subdials), the 7734

(with date), and the 7736 (with 12-hour subdial) made between 1969 and

1978. Almost 2 million of these movements left the factory, destined to

tick away merrily in watches made by such names as Hamilton, Helbros, Le Jour, Memosail,

Wittenaur, and Breitling.

It should be noted that any resemblance between the 7733 in the photo opposite and what's in the Felicia is purely coincidental. The one in the photo is a modern revival used by the German manufacturer Jörg Schauer in one of his chronographs. The movement in the Felicia was never intended to be seen by its owner. But they both do the same job.

Note the use of wire springs at various places around the movement. Some enthusiasts regard this as a weakness in the design, as they can go out of adjustment. Still, the ubiquitous 7750 movement ( an automatic-winding descendant of the 7733) uses the same springs but nevertheless has a well-earned reputation for ruggedness and reliability.

Felicia in Australia

IN TRYING TO FIND OUT some more about Felicia my researches led me to a Mr Charles Springer. Mr Springer was the sole importer of Felicias into Australia from Switzerland from 1949 to 1985. He's still working in his office in Sydney, and that's where I phoned him with a request for information. He was extremely helpful and generous with his time. He told me that Felicia was originally a small independent maker in Switzerland, but was now part of the SMH conglomerate. (He seemed amused at the thought that SMH started out as "a bunch of Germans importing coffee into Europe".) To my suggestion that Felicia's products were perhaps "middle of the road" in terms of quality he emphatically responded no, they were "top quality", and that at one stage 65% of all mechanical watches sold in Australia were Felicias. Furthermore, nearly 100% of all nurses' watches (the 'upside-down' ones they pin on their uniforms) sold in Australia were Felicias too. Obviously they weren't in the top luxury bracket, but he believed they were sturdily made using quality materials, and very good value for money. Based on the one I had in front of me, I had to agree with him. Interestingly, he said he had plans to begin importing mechanical Felicias again, with either ETA or Ronda movements. I asked him what watch he had on at the moment. He seemed surprised at the question. "A Felicia, of course," he said. "All stainless steel, 200 metres water resistant. Came in handy when it was my grandchildren's bathtime!" I queried whether the 200 meters water resistance was genuine. "Should be, provided the seals are OK," he said. I didn't tell him about my watchmaker's reservations.

Living with the "Chronographe"

My first impression was how comfortable the watch felt on its rubber strap. Instant adjustment is of course available via the simple stainless buckle, and there's plenty of it too: those with beefy wrists need have no fear of 'wrist strangulation'. I had imagined that rubber would cause my skin to sweat in the 40°C heat we've been having recently, but to my surprise I found this didn't happen. And no hairs pulled either! And while rubber wouldn't look too good on a dress watch, it suits the sporty image of this one perfectly. The two loops both slide along the strap independently, and so keep the end neat.

Overall legibility is excellent thanks to the thick, white-painted hands and relatively uncluttered dial. Even without my reading glasses I could make out the time in all but the dimmest situations. The hour markers are tritium filled and the hour, minute and sweep seconds hands have tritium inserts, but with the passage of time its efficacy has diminished more than somewhat.

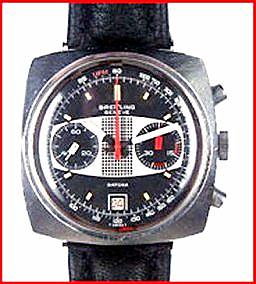

The 'cute' blocky subdial hands, so very 70s, are surprisingly effective and I actually think they're easier to read at a glance than the 'normal' ones. They take a bit of getting used to, though. Quite a few manufacturers used them in the late 60s and early 70s, including names like Heuer and Breitling (that's a Breitling Datora below left, and a pinked-tipped Chrono-matic below right. I think the styling department must have been out to lunch that day.) Actually the styling of the Datora case is remarkably similar to the Felicia's. The Datora uses a Valjoux 7734 (same as the 7733 but with a date window).

Operating the chronograph buttons was uneventful with everything functioning as it should, including the resetting mechanism. The 30-minute subdial is of the 'jumping hand' type (i.e. the hand moves around one notch as the sweep second hand passes the 12 o'clock position), and the other subdial is running seconds. The 30-minute subdial has the first 10 minutes divided into a blue 5-minute sector and a red 5-minute sector, and these are further marked at the 5, 3 and 1 minute countdown positions. I believe this is to do with yacht racing, but I stand to be corrected on that. A close inspection of the subdials reveals them to be sunk into the main dial, and engraved with concentric rings.

On the outer edge of the dial is the tachymetre scale which has small but

legible numbers (for those with good eyesight), but the small, red numbers

comprising the telemeter scale just inside the minute ring are very hard for my

poor old eyes to

distinguish. (A telemeter scale is used to determine the distance to an

event giving out both light and noise, such as lightning. The chronograph

is started at the light flash and stopped when the noise is heard. The

number on the scale opposite the sweep seconds hand then gives the distance—in

this case, in kilometres.)

On the outer edge of the dial is the tachymetre scale which has small but

legible numbers (for those with good eyesight), but the small, red numbers

comprising the telemeter scale just inside the minute ring are very hard for my

poor old eyes to

distinguish. (A telemeter scale is used to determine the distance to an

event giving out both light and noise, such as lightning. The chronograph

is started at the light flash and stopped when the noise is heard. The

number on the scale opposite the sweep seconds hand then gives the distance—in

this case, in kilometres.)

The bezel has a luminous dot at the 60-minute position, rotates in both directions and has no indents. Its action is

smooth but with enough resistance to prevent accidental movement. It can

fulfill 3 functions: as an elapsed-time recorder, as a date indicator,

and (with a little imagination) as a second time zone indicator.  The bezel is unusual in that it doesn't sit flat on the case top; it sits

2mm above it with its collar painted black (see photo). Being slightly

raised in this way makes the bezel easier to grasp and turn.

The bezel is unusual in that it doesn't sit flat on the case top; it sits

2mm above it with its collar painted black (see photo). Being slightly

raised in this way makes the bezel easier to grasp and turn.

The all stainless steel case has a slightly curved profile to fit the wrist, and while both it and the screw-in caseback are substantial the watch is not overly heavy at 100g (3½ oz). As mentioned previously, it is extremely comfortable to wear. The case is polished all over except for the top, which has a circular brushed effect. The flat central portion of the caseback is also brushed, and has managed to collect a few light scratches, but nothing serious. The caseback reads: Stainless Steel - Water Resistant 20 ATU - Incabloc - Swiss Made - 14012 /1. The 6mm diameter crown does not screw down (neither do the pushers) and has no crown guard, but is easy to grasp. Winding the movement is easy and smooth.

The convex acrylic crystal protrudes about 3mm above the bezel, further adding to the vintage look.

The Valjoux 7733 keeps ticking away quietly, losing 12-13 seconds a day. This in itself is quite acceptable, but the consistency of the loss leads me to suspect a little regulation could improve the accuracy still further. The movement doesn't hack, but steady backwards pressure on the crown will eventually induce it to stop, thereby allowing setting of the time to the second. But in keeping with the vintage ethos, who gives a rip?

To sum up

To me, the Felicia de luxe Chronographe is a good example of traditional mid-price Swiss watch virtues—reliable, rugged, useful, attractively designed and value for money. During the two-week review period it became a favourite for daily wear, not the least because of its comfort. It soon became a source of satisfaction upon waking in the morning to give the Felicia its daily wind, thereby assuring its smooth running for another day. No worries about the state of wind like you can get with an automatic! The power reserve is a useful 46½ hours, by the way.

The chronograph is a handy feature for timing anything from boiled eggs to parking meters. I would have preferred to have a 12-hour subdial as well though.

The one unknown factor is the true water resistance of the watch. I didn't subject it to any testing so I can't say for certain, but I think I would take my watchmaker's advice and be careful with it around water.

Over the years Valjoux movements (especially the cal.72) have been used in many prestigious makers' watches, including Rolex. The Valjoux 7733 chronograph movement is tried and tested, and parts are easy to source if required. My experience with it in this watch has been entirely positive.

Specifications

Movement: Valjoux cal. 7733 17-jewel manual-wind 2-register chronograph, monometal balance with flat hairspring. 31mm dia., 6.0mm high, 18,000 bph, Incabloc shock protection. Power reserve: 46½ hours (chrono. stopped); 44¼ hours (chrono. running).

Case: Stainless steel, 40mm wide x 42mm long, 20mm between lugs. 38mm dia. bi-directional rotating bezel, screwed caseback. Non-screw crown and pushers. Acrylic crystal. Total thickness 14mm. Weight including rubber strap 100g (3½ oz). Claimed water resistance 20 ATU (atmospheric units) or 200 metres (but see text).

Acknowledgements

John Gaskin of Adelaide Time Watch & Clock Repair Specialists, Adelaide, South Australia for the loan of the watch.

Uhren Magazin (April 1999) for the photo of the Valjoux 7733 movement.

Richard Smith for the photo of his Breitling Datora.

Eric Katoso Vintage Watches for the photo of the Breitling Chrono-matic.

© Les Zetlein, January 2000. All photographs other than those listed above were taken by me using a Sony Mavica FD-83 digital camera.

Any comments or corrections? Then please...

Last update 21 Jan 2000